A vibrant space shaped by sensations

Review of the exhibition I was listening to you. UiT The Arctic University of Norway – The Art Academy Graduate show 2022 (bachelor’s and master’s), Tromsø Kunstforening. Curated by Kristin Tårnes and the students. Tromsø, 13.05.2022 - 29.05.2022.

Overall, the works of this year’s graduates burst with energy and reflected approaches to subjects and materials. Albeit diverse, surprisingly many connect and speak to the senses, through vibration and sound.

By Lena Gudd

This exhibition feels full of life, from the exciting opening to the different performances, guided tours, concerts and events. This liveliness seems to be rooted in the connection between the exhibited art works — the sound of one work connects with the visuals of another, the calmness of one installation is framed by the vibration of the neighbouring art work. Life, as it unfolds at the very moment of experiencing the exhibition, becomes part of it as well, through sound, sight, smell and touch in very subtle ways. Time and empathy are needed to notice this fragile web.

Questioning memories and rewriting stories

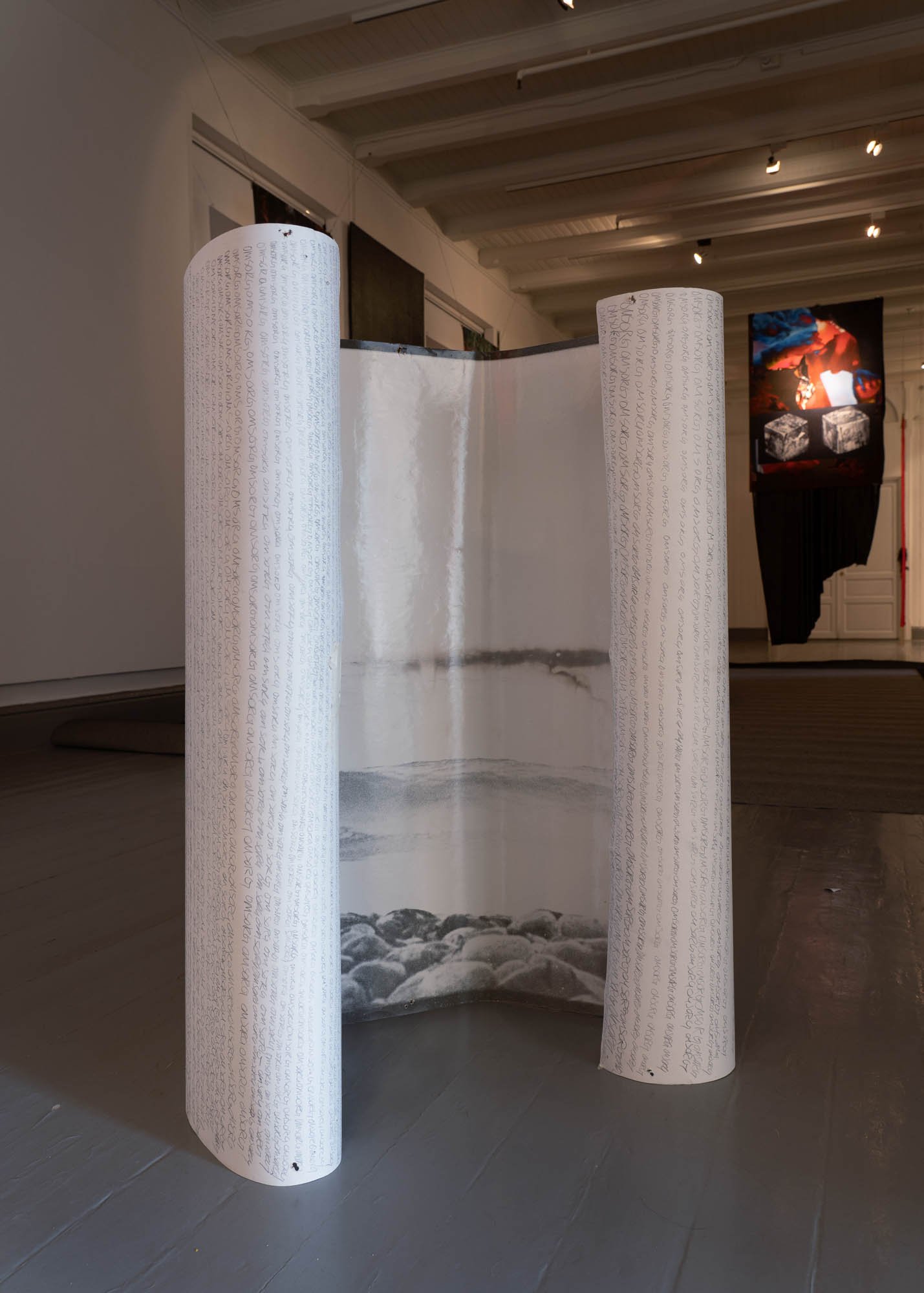

Entering the space of Øistein Sæthren Dahle’s work Tyst Aske/ Mute Ash is like stumbling into his studio. It is as if I’m roaming around in the intimacy of a work in progress. Large-scale analogue photographic prints are nailed to the shorter wall, two pinned at the side walls and two laid, as if stored, on the floor.

With what looks to me like a deliberately unfinished work, he is indeed dealing with a subject that is in process — namely his grief over a dear friend’s death. To deal with his longing and sorrow, the artist engaged with his friend’s photographic archive as a starting point, from where he introduced his own photographs, as well as sound, video and handwritten material. The almost human size analogue prints are mainly black or red, which leaves me wondering if the colours conceal any motives under their surface. Other black & white prints are overexposed, low in contrasts and with few details. I seem to look at landscapes, a river and forests maybe. The only occasionally occurring sound and video elements catapult me back from the studio experience into the exhibition space.

Almost unnoticed – because it is placed close to the next art work – a speaker releases every now and then the Norwegian words “omsorg, omsorg, omsorg ”, which can mean ‘care‘ or ‘about grief’. A fitting wordplay that is also handwritten in long chains on the backside of a print standing on its side. Instead of rendering visible, photography becomes here a driving force of guidance through its very materiality, embodying a range of emotions.

Following the sound of the loudspeaker, I am stumbling again, this time over the edge of a carpet, into Henrik Sørlid’s piece Remembering the Gods of Ancient Grease. The title – and what must be an intended pun – refers to Greek mythology, and forms the underlying theme in his work: that history is a constructed and subjective story, a suggestion, to be possibly written anew and surely not be taken too seriously.

Grey carpets on the floor and on one of the two walls create a space within a space, with the cosiness of a living room. Six large colourful collage works frame this room, two of them sheltering a TV screen, almost shrine like. The works form dreamlike worlds, landscapes or newly composed stories. I distinguish elements of early history as taught in school books such as rock carvings, a mummified face and an ancient vase. They seem to be rewritten together with references to the natural world like reptiles, tropical forests and lichen together with many unidentifiable colourful bits and pieces.

After some pondering upon the complexity of remembrance and our relation to the so-called historical facts, I surrender to the surreal images in Sørlid’s film, made partly from archive materials, and let it take me to his psychedelic sci-fi world of neon colours.

On a family quest

Walking up to the first floor, the first thing I see is a white dress with a red blouse. In her work Deathspell The Search for the Cursed Ring — Part I, Marie Saure is dealing with her family history, engaging with an amber ring that her grandmother thought of as cursed, since she had seen a correlation between herself and two other female family members wearing the ring and getting cancer. The ring was subsequently buried so that it could no longer do harm. Engaging with this story, Saure has been sewing a dress based on a Bunad, a traditional costume, and embroidered what looks like local seaweed, lingonberries, a blueberry, a coltsfoot and a snake on it. This is apparently the magic formula that might have bewitched the ring, although the ritual looks unfinished. The number on the front of the dress — 1895 — does not, as assumed at first sight, designate a year, but is a family number that helps find other members with the same genetic defect. After a while, I notice the ring — embroidered on the dress’s pouch, in the midst of several layers of flames.

The dress dangles on a thread from the ceiling and seems to constantly turn around itself, slowly and steadily, which gives it a ghostlike aura. Next to it stands a chair, that could have easily come from her grandma’s home, with a neighbouring TV screen showing Saure’s relatives searching for the buried ring. Unsuccessfully it seems. Part I says the title — the quest for the ring is to be continued.

Rooms of relations and vibrations

I almost missed the depth of Annika Sellik’s installation, whose essence extends to the whole room. The fact that visitors can circulate through it makes the work more fragile and easily overlooked. It would have benefited from a closed door to preserve its wonderful subtleness.

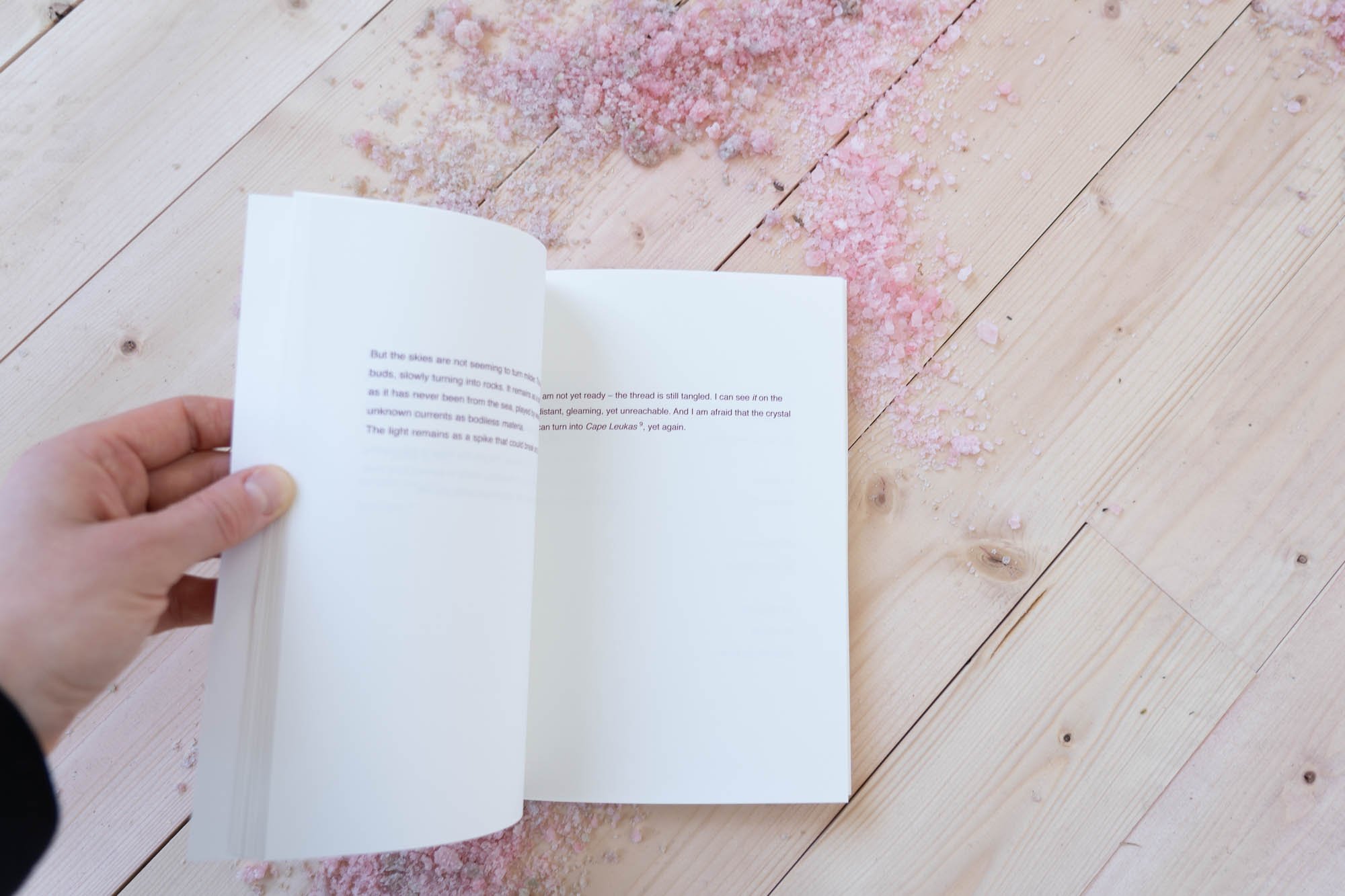

Sellik’s work, entitled En Météo du Sens, invites me to slow down and take time with the materials and sensations it evokes. The elements of the installation are revealing themselves like layers peeled off an onion. First, I notice only the pink salt on the floor, as well as the sound, supposedly coming from a bowed string instrument, built and played by the artist herself. Two surface transducers turn the floor into a speaker, conducting the sound’s vibration right into the uneven wood panels. Slightly tinted in pink, they vibrate with the sounds of her instruments. The floor carries the salt, which was made by evaporating seawater from a local fjord and then dyed with rowanberry juice. Layers and layers come off, unveiling a close attention to the natural world and its materials, mingled with sound, vibrations and smell, as well as Estonian oral traditions. The latter I find on the floor in a poetry book written by Sellik in Estonian, French and English. The light seems to be part of it all, reflected by the meticulously newly painted walls and the bright wooden floor. Once aware of its complexity, this work draws me into a whole new universe.

Sellik's installation resonate inside me while I move into another space. What seems to be a giant transport box made out of plywood, turns out to be the room of all rooms of this exhibition. Curiously, I am entering Matias Frøysaa’s container-like box from the side, stepping into a twisted wooden cave or womb, going in and up and around until sitting in the dead end, a sort of mezzanine. Entering this space reminds me of children's books where the reader climbs through a frame of sorts and into another dimension. From the inside, the container is lined with wooden tiles that have a certain roughness to them. This brings forward a feeling of deliberate unfinishedness.

Box 4/7 (I Do Not Want to Become a Plastic Bag) becomes a different space for every visitor. For me, it evokes an inwardness at the same time as it connects to the exterior through the sound emitted by other art works and from visitors passing by. Frøysaa questions, in this powerful sculpture, the relation to rooms and space by having the visitors physically experiencing the art work, letting them be transformed by the room and transforming the room in return. The other day, the box even turned into an instrument during a concert with the musician Zatoshi Zlackamoto, organised by Frøysaa.

Today the box room smells lovely like freshly cut wood and – on sunny days, at least – it has this soft light coming from the big window opposite the entrance. It is a place that invites to stay.

A hole for alternative listening

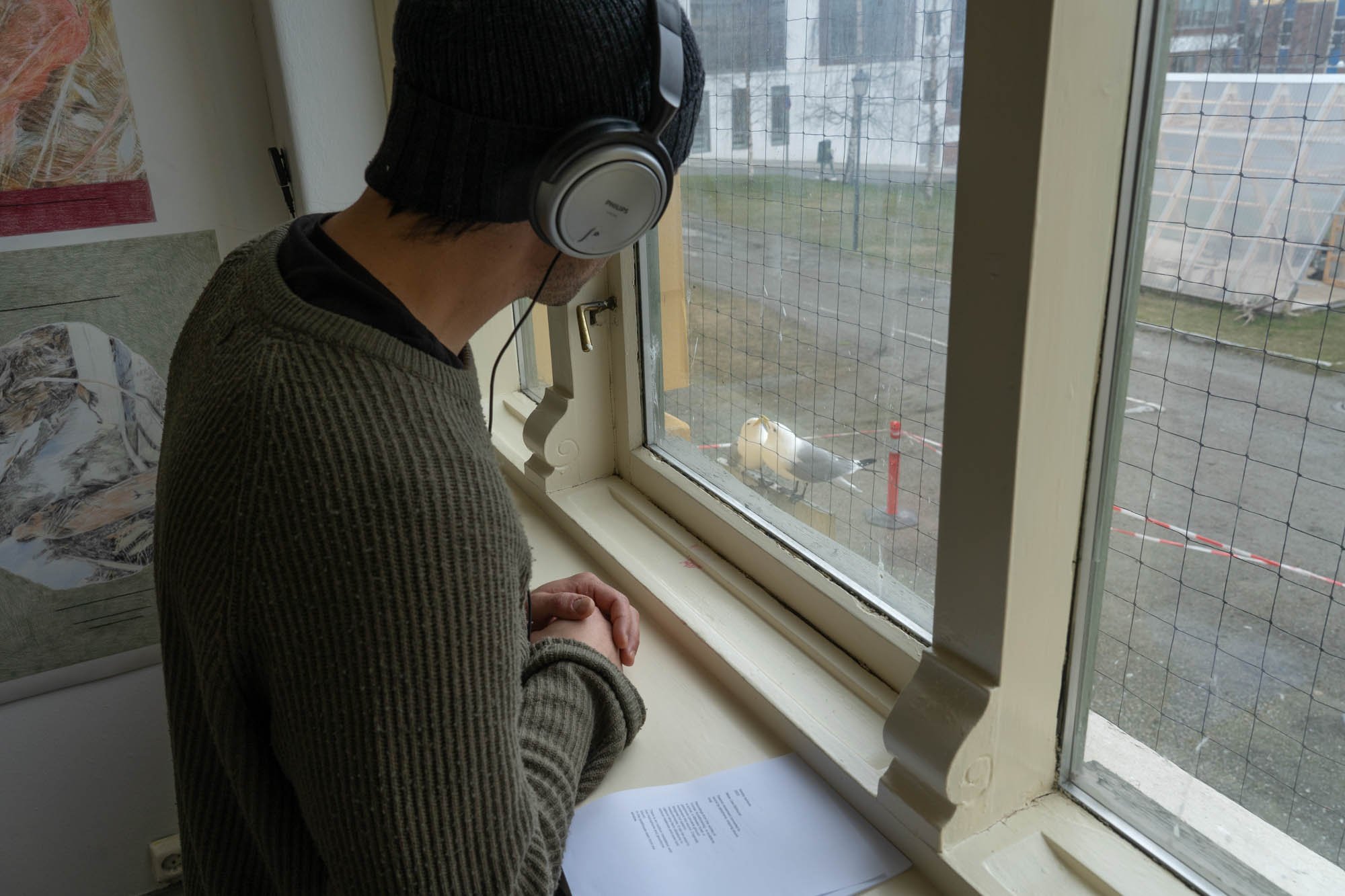

One piece of Maija Liisa Björklund’s work Worldly currents is quite discreetly placed in the window sill of the Mondo bookshop. A headset is playing recordings of a local car tunnel, the kittiwake hotel outside Tromsø Kunstforening, as well as the metal palm sculpture next to the building in a loop. A note next to it tells me that the sounds originate from a geophone, a device that converts seismic ground movements into sound.

From that window, I am looking down at the museum park and the triangular “boathouse” – a sculpture, left from an earlier exhibition. In its centre, Björklund has dug a square hole into the ground, just big enough for one person to sit in it. Three speakers play live recordings by microphones and geophones attached at the entrance. This blends in with the sounds that I make out from ordinary life, like screaming kittiwakes, people chatting or cars passing. Sitting in the hole I hear, through the loudspeaker, the vibrations of people walking nearby, translated by a geophone into sound waves.

All these sounds and vibrations blend and become indistinguishable. This makes me feel like having a different sense of hearing, somehow sharpened but at the same time as if lacking the capacity of making sense of it. It is difficult to distinguish which elements belong to the art work so that everything seems somehow to become part of it. Through her immersive installation, inviting the listener down into the earth, Björklund presents us with alternative ways of listening, with deep listening.

This is where the circle seems to be closing. To begin or end the visit with Björklund’s sound installation is setting the basis for the vibrant art works of this year’s graduates of the Tromsø Art Academy.