wearable sculptures and speculative cosmology

Interview with artist Erin Sexton about her art practice and the exhibition & workshop Contingency Planning (live-streamed event due to the Covid-19 pandemic), Kurant Visningsrom, Tromsø, 19.03.2020 – 20.03.2020

Written by Eleni Ieremia

«I have always preferred to position myself at the edges of things, where it is a bit more wild and open, less defined. It is certainly more work to live in the woods, ensuring trees don't fall on your house, stopping ants from eating it, etc., but there is much more space to explore different ways of being. I think big cities, however wonderful, cannot just keep on growing. We need to focus on forming smaller, more localized communities, and there are lots of cheap old farmhouses around» – Erin Sexton.

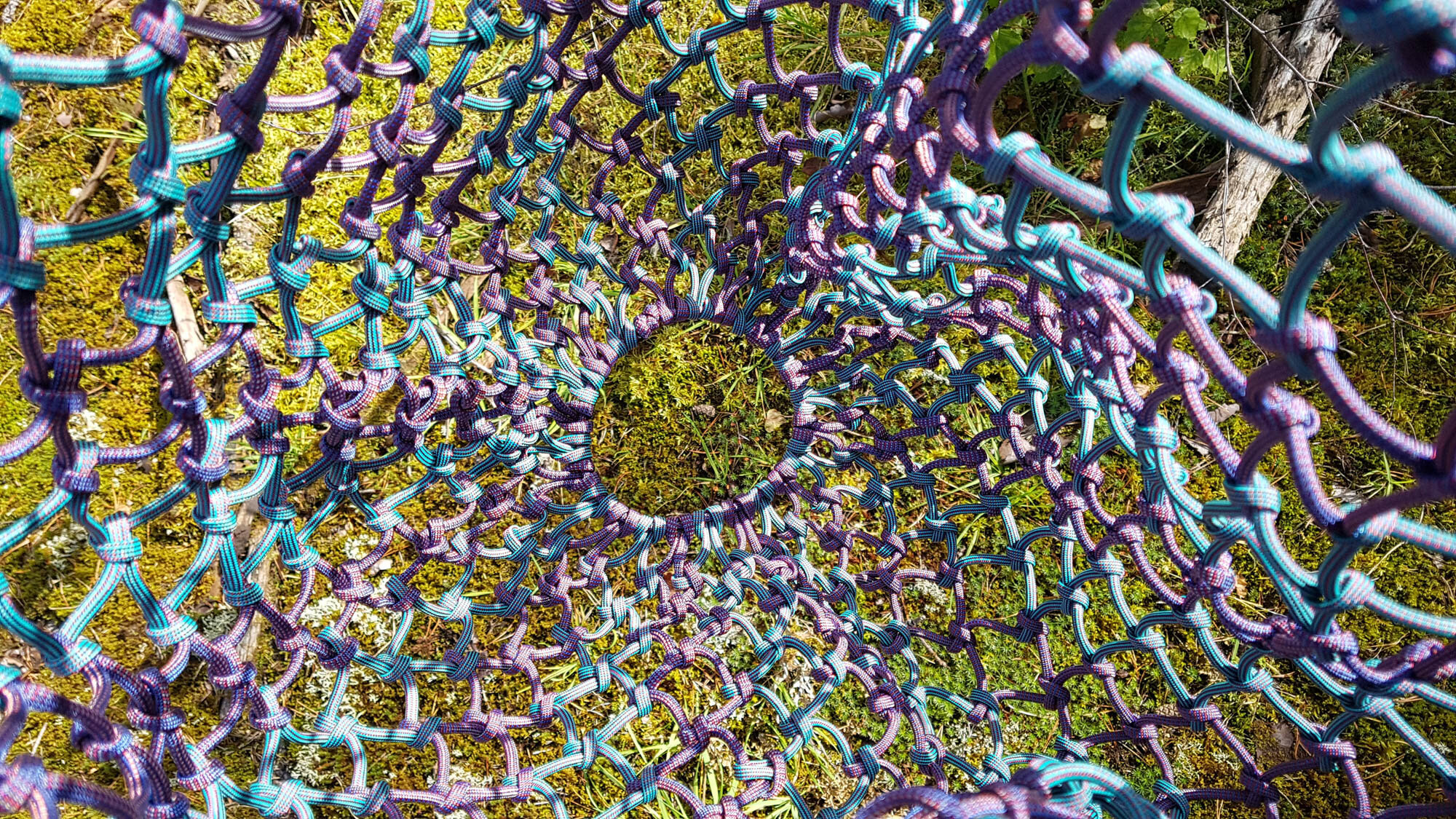

Konstnären Erin Sexton (CA) är baserad i den yttre delen av Oslo och för närvarande arbetar hon med att bygga upp en ny studio i skogen en bit utanför huvudstaden. I sin konstpraksis är Sexton upptagen av den rituella kraften i att arbeta kollektivt och tvärvetenskapligt, i samarbete med olika professioner. Hennes installationer består av funnet material och skulpturer som återskapar en form av spekulativ kosmologi. Det är ett konstnärsskap genomsyrat av ett narrativ som beskrivs som science-fiction-survivalism. I projektet, 'Contingency planning’, undersöker Sexton hur vi kan arbeta med krishantering som narrativ, hur vi kan skapa hjälpverktyg och metoder för en osäker framtid eller föreställa oss andra världar. Hon har utvecklat projektet tillsammans med dansaren Yohei Hamada. Det var tänkt att samarbetet skulle presenteras som en utställning på Kurant Visningsrom i Tromsø (mars 2020), men med anledning av Covid-19-utbrottet, blev det en tvådagars workshop med konstnärerna över Twitch och Discord. Yohei Hamada live-streamade en danskoreografi utomhus, i en mystisk skogsdunge någonstädes i Belgien. Deltagarna vid andra sidan skärmen fick diskutera och prova på metoder i hur man kan arbeta med kroppens rörelse, sinnesupplevelser och meditation. Erin Sexton höll i en föreläsning och live-radio performance från hennes studio. Över datorskärmen fick vi se henne demonstrera hur man kan bära hennes skulpturer, rörelseövningar och instruktioner på energiexperiment tillsammans med de bärbara objekten. Sexton har producerat dem utav fallskärmslinor som hon knyter samman med en avancerad knutteknik och nätbindning. Skulpturerna sägs expandera vår perception, ge oss verktyg till nya förmågor, samtidigt som dem ger oss beskydd.

Intervjun ägde rum på engelska.

Eleni Ieremia: I would like to begin the interview with a slightly odd question, were you a weird kid?

Erin Sexton: Yes, I was very shy and mischievous, also quite nerdy. My best friends were my rock collection and Sonic the Hedgehog. When I wasn't trying to channel magical rainbow crystal powers or jumping through rings into hyperspace, I was pouring through my father's extensive sci-fi novel collection. I also spent a lot of time staring at the sky, trying to feel the spinning of the earth, to relate my body to the immenseness of space, and searching for UFOs of course.

EI: With your background as a licensed radio operator, how did you become interested in working with radio noise and electromagnetic energy?

ES: My grandfather introduced me to amateur radio as a child in the pre-internet era, so it made quite an impression. Radio noise is quite literally the sound of space, including traces of every celestial event since the big bang, mixed with all of our own transmissions, swooping around at the speed of light. It's absurdly unfathomable. I used radio and electromagnetic interference in my work for many years before I finally got my license in 2015. I also have several Reiki practitioners in my family, so my understanding of 'energy' has always been quite open. We emit fields too, our bodies and minds are electric, flowing into that swirling swooping invisible realm.

EI: I know you have been working with sonified brainwaves together with amateur radio in your work ”NOÖSPHERE” (2017). How was this sound piece made?

ES: 'Noöpshere' was a very playful engagement with all this, a sci-fi expedition / ritual / experiment resulting in an installation at Lydgalleriet in Bergen and a book. Two artist friends' brainwaves were bounced off the ionosphere from Bergen Kringkaster, their EEG data 'sonified' with cheesy 90s midi samples. There were also crystals and tinfoil involved. I was set up at a field station in Svartediket valley, receiving the signals, coordinating via radio, and recording the whole process. For me, this project was a meditation on the limitations of our technology, how our brains and the cosmos are so much more complex than any system we could hope to design. This led me to focus more intently on what we are already transmitting anyhow without the need for gadgets or interfaces.

EI: Paracord rope is a recurring material in your art, could you tell me more about why you are using this specific material?

ES: Radio is magic, but knots are my favorite technology. I work with all kinds of ropes, but the cultural references of paracord are key to my practice right now. Parachute cord is a nylon material that was originally developed by the U.S. military. WWII paratroopers would drop behind enemy lines and salvage the cord for many survival uses, also making bracelets to help pass the time. Paracord 'survival bracelets' are now very popular. In the event of an emergency, the bracelet can be unravelled and the cord used for whatever is needed. But how effectively? And to what end? As I see it, if we don’t resist capitalism and the military industrial complex, we are at a cultural, ecological, and evolutionary dead-end. Wilderness survival skills are important, but before we safely shut down all nuclear reactors, they don't count for much, sorry to say. We need to transform the society that we have,to regain our sense of collectivity and agency, not to be sidetracked by doomsday prepper nihilism or 'back to nature' idealism... These are the narratives I am trying to shift in my work with paracord.

EI: Your project, 'Contingency planning' is somehow relevant at this moment, in the times we are living in.

ES: Yes, unfortunately so at this moment. However, this project was intended to playfully subvert fear, scarcity-based apocalyptic narratives, and to gently push towards a paradigm shift in our understanding of mind and collective agency. I do still feel some space for this approach, but the issues are now far more sensitive and pressing.

EI: In this project you have created objects from paracord ropes, tarpaulin, netting tools and more. How are these harnesses used in this context?

ES: Tarpaulin for me is a symbol of basic protection, ubiquitous and inexpensive. With a few knots and folds, it creates a simple safe space for other things to become possible. My paracord harness works are an extension of this concept, linking more directly to the body, like a metaphysical prosthetic. The popularity of paracord means it is available in a virtually infinite array of colors and patterns. I choose the most psychedelic combinations, knotting them into complex forms involving many straps and buckles attached to large globular nets. They are meant to be worn over the head, connecting in different ways to the body.

EI: The 'Contingency Planning' project also included a live-stream movement workshop by dance artist Yohei Hamada who you collaborate with. What can Hamada's expertise in dance and movement add to your practice?

ES: Yohei’s movement research really adds another dimension to the workshop, helping to ground the project in the physical, focusing on body awareness and subtle gesture. He also really helped me to flush out the metaphorical function of the nets: When an actual or imaginary pressure is applied to the body, and we are aware of it, we can adjust our movement and use that force to give us more strength and stability. I relate this to the difficult and paradoxical situations we are now caught within. Perhaps if we can imagine these pressures in a more physical sense, it could help us to cope with future anxiety, finding ways to redirect our energy and support one another.

EI: You knot these wearable sculptures/harnesses and they seem incredibly time consuming to produce. What happens during the working process?

ES: Yes they are, especially the straps, but it's also quite meditative. I don't have to think about the knots, they have become automatic, but the works do require a lot of planning, measuring, and testing. I am constantly negotiating between my aesthetic sensibility / desire to explore form and finding the right scale / strap angles needed to comfortably connect to the body. The biggest challenge has been to my own perception of dimensionality: starting with 2D measurements / drawings, catching my errors shifting that to a complex knotted 3D curved space, then considering motion, and finally discovering all the inversions and different possible connections that arise from the final form. It's cozy and fun to think about hyperspace, floating crazy geometries, and other realms beyond. But I suspect that things are far more messy and wild, and that we are in it. Mathematics and technology have really broadened our understanding of the universe, but I think the next step requires a more complex and intuitive system, one that we already have intimate access to. I feel that we need to restrain our skepticism a bit and seriously explore consciousness and perception. It could solve a lot of problems and bridge so many gaps. However I think the time for wearable or publicly sharable sculptures might be over... We will see. There are many other methods.

EI: New materialist thinkers argue that both nature and humans act, both are active in the world and in its progress. Andreas Malm is claiming in his book, 'The Progress of This Storm’ (2017), that new materialist thinking is undermining our ability to act and master climate change when everything is having agency. He argues that this non-contrast between nature and humans leads to a deprived sense of responsibility for humans to take action. Do you believe posthumanist and new materialist thinking can give us an opportunity to deal with and make sense of crisis situations? Is your art practice influenced by new materialists or posthumanist thinkers?

ES: Haven't read him, but I certainly wouldn't blame new materialist thought for our inability to adapt, but rather capitalism, dualism, etc, etc... That being said, I do find some of it a bit trite, but still, why waste energy attacking philosophy nerds and artists? There are far more problematic forces to fight, and we need all the allies we can get. Jane Bennett ('Vibrant Matter’, 2009), Quentin Meillassoux ('After Finitude' / 'Science Fiction’, 2009 and 'Extro-Science Fiction’, 2015), Timothy Morton (’Hyperobjects’, 2013), and Karen Barad ('Meeting the Universe Halfway’, 2007) are the thinkers from that realm that have had the strongest impact on my practice. I definitely think that these philosophies can help us to be more humble, open, flexible, and resilient. Confronting complexity and rethinking old paradigms is difficult and takes a lot of energy, but it is essential and also very liberating. If we resist change and allow fear or denial to take over, at the very least we lose our capacity to be responsible and effective. All complex systems have agency, they act, they affect things. They don't tolerate endless inefficiency and destruction, they self regulate, they evolve beyond it. We need to get on board with that, or we will be left behind.

EI: I have to admit that I suffer from what is called a twitter-brain. I feel I’ve lost the coherent narrative. The micro-stories are all over the place in cyberspace, creating a global narrative collapse. At the same time, the crisis reveal problems that our societies are dealing with everyday. This means there is potential to organize politically on a global scale to actually change our narrative and not go back to normal after the worst part of this corona pandemic. You use sci-fi literature as a reference point in your art practice. Can fiction help us figure out ways of handling pandemic disasters and severe recessions? Do you think the current pandemic will find its way into your work?

ES: If we can manage to filter out the garbage and ignore the vamps and trolls, maybe some good can come out of this oversaturation. There are a lot of narratives that need to collapse right now. This pandemic is a terrible wake up call, forcing a pause in business as usual, and yes, lifting the veil to reveal how capitalist fictions have destroyed our society. We absolutely need to take this opportunity to organize and create something better. Even the pope just called for universal basic income. We can do this and much more, hopefully in a calm and balanced way.

Good science fiction is a form of contingency planning, running through different possible scenarios, exploring problematics and possibilities. It is a very powerful tool for expanding our scope and healing old wounds. There is much brilliance and also some brutality in Octavia Butler’s writings. I highly recommend her 'Patternist series' (1977-1984), which delves into the use of psychic abilities to survive an extraterrestrial plague. Frank Herbert’s ’Destination: Void’ (1966) and the ’The Pandora Sequence’ (2012) with Bill Ransom is incredible, exploring the dangers of artificial intelligence and war-like mentalities. The protagonists manage to save humanity by evolving collective consciousness with the help of giant psychedelic jellyfish aliens.

If we can continue with the wearable harnesses, I think facemasks and strict protocols will need to be involved. I feel this pandemic will change how we work in many ways, perhaps affecting the artistic positions we take, and causing a shift in our priorities.